I.5.11

8/24/2021

So I'm going to set

| f | = x2 - xz - yw | |||||

| g | = yz - xw - zw | |||||

| h | = y2z - x3 + xz2Y | = Z(f,g) | ||||

| X | = Z(h) - (1, 0,-1) |

And the "projection from a point to a plane" is defined back in 3.14....

which.... I didn't do....

"What happened to 3.14?" It broke my heart. Well, every exercise breaks my heart. The holeinmyheart just gets bigger and bigger. Soon, it will be wide enough for some very fancy ero guro.

Okay, great. By the way: If you're sick of my writing, think of it from my perspective. In order to do these exercises I have to constantly look back at previous exercises for reference. And since my only record of doing these exercises is this very blog, I am often forced to reread my own shitty words... over and over.

"Ummm, maybe just do the math instead of being a creep?"

NOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO. NEVERRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRR. *undresses* Listen: I've read a lot of self-help in my day, and one of the foremost pieces of advice has been to sprinkle the mundane stretches of work with rewards. So when I write something like *FuCks you in the butth0l3*, that's my hard earned reward for all the back-breaking mathematical work I've done. Yes, when I write *Strokes your hair and smells it*, or *Passionately kisses you on the lips*, or *unzips and starts filming*, or *breathes sex noises into your ear*, or I SAID PULL DOWN YOUR FUCKING PANTS, YOU PRUDE. MY TONGUE IS COLD. I NEED WARMTH. *PANT PANT PANT* GIVE. ME. YOUR. BUTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT, please don't mind. It's just my rightful reward for doing algebraic geometry.

Well, in the case of this exercise, the so-called projection is very simple. It's just

| ϕ : P3 | → P2 | ||

| (x,y,z,w) |

(x,y,z, 0) = (x,y,z) (x,y,z, 0) = (x,y,z) |

I.e. "drop the last coordinate" (set it equal to 0). (To see this, draw out the

case of P2 → P1, projecting from (0, 0, 1) to z = 0).

Now I'm going to show that it does restrict to a map Y → X. Let

Q = (x,y,z, 1) ∈ Y (Yes, we can assume w = 1 wlg), so it satisfies f and g.

Specifically:

| x2 - xz - y | = 0 | (1) |

| yz - x - z | = 0 | (2) |

So

| g(ϕ(Q)) | = g(x,y,z) | |||||

| = y2z - x3 + xz2 | ||||||

| = (x + z)y - x3 + xz2 | (subbing (2)) | |||||

| = (x + z)(x2 - xz) - x3 + xz2 | (subbing (1)) | |||||

| = x3 - x2z + x2z - xz2 - x3 + xz2 | ||||||

| = 0 |

Hence, ϕ(Q) ∈ Z(h)... almost as needed. We do need to show that

(1, 0,-1) isn't in the image in order to show that it's contained in X. This is

easy though. An element that maps to (1, 0,-1) would have to be in the form

Q = (1, 0,-1,w), and if Q were in Y , it'd have to satisfy f. But

| f(Q) | = 0 | ||

| ⇔12 - (1)(-1) - 0w | = 0 | ||

| ⇔1 + 1 | = 0 | ||

| ⇔2 | = 0 |

which is a contradiction obviously. Hence, we can indeed write ϕ : Y → X.

Next, I'm going to show that ϕ is bijective. First, is it injective? In my notes, I

wrote "well, duh", which is retarded. It's not trivial or obvious to the point of

saying "well, duh", so that was fucking stupid, and I guess I have to figure it out

now. Sorry, sometimes thinking of projective coordinates sends my head for a

spin. Let's suppose Q = (xq,yq,zq, 1),R = (xr,yr,zr, 1) ∈ Y , and suppose

ϕ(Q) = ϕ(R) i.e. (xq,yq,zq) = (xr,yr,zr) as projective points. So really, we

have

| xq | = sxr | ||

| yq | = syr | ||

| zq | = szr | ||

for some scalar s ∈ k (s≠0). If s = 1, we're done, so assume s≠1. So I'm just

going to denote x = xq,y = yq,z = zq for simplicity. Since these two points

are both in Y , they satisfy f and g.

| x2 - xz - y | = 0 | (3) |

| yz - x - z | = 0 | (4) |

| s2x2 - s2xz - sy | = 0 | (5) |

| s2yz - sx - sz | = 0 | (6) |

| (7) |

Okay, take (5), divide by s, add y to both sides, and you get

| y | = sx2 - sxz | (8) |

| (9) |

Now, plugging this into (3), we get

| x2 - xz - (sx2 - sxz) | = 0 | |||||

x2 - sx2 - xz + sxz) x2 - sx2 - xz + sxz) | = 0 | |||||

x2(1 - s) - xz(1 - s) x2(1 - s) - xz(1 - s) | = 0 | |||||

x2 - xz x2 - xz | = 0 | (Used the s≠1 assumption to divide by 1 - s here) | ||||

x2 x2 | = xz | |||||

Now, plugging this identity back into (3), we get

| y | = 0 |

Now plug this into (4):

| 0 - x - z | = 0 | ||

x = -z x = -z |

So ϕ(Q) = (x,y,z) can be written as (x, 0,-x). We must have x≠0

for this to be a projective point, but in that case we could divide by x

and see it's the same as (1, 0,-1). But we know that this isn't in the

range of ϕ!. So we must have s = 1. I.e. Q = R. Hence, ϕ is injective!

Okay, now for surjectivity (which will also give us a formula for an inverse). Now,

isn't it weird to have to come up with an inverse for

| (x,y,z,w) |

(x,y,z) (x,y,z) |

you're telling me I need to start with (x,y,z) and "recover" the w? I need to

produce the w myself!? Daaaang. Well, this certainly wouldn't even be possible if

there were not some restrictions on what w can be, and that is determined by

where the point (x,y,z,w) comes from in the first place–i.e. Y = Z(f,g). In

fact, if we look at

| 0 | = x2 - xz - yw | ||

| 0 | = yz - xw - zw | ||

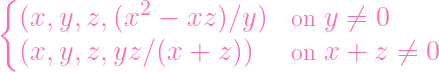

We can actually get two "formulas" for w

| w | = (x2 - xz)∕y | (10) |

| w | = yz∕(x + z) | (11) |

Now, there are several problems here. First, of course, we have two formulas.

Not one. Secondly, we're dividing by stuff (y and x + z), and we don't know if

those things could be 0. Let's just assume for now that y,x + z≠0. Then check

this out

| (x2 - xz)∕y | = yz∕(x + z) | ||

| ⇔(x2 - xz)(x + z) | = yzy | ||

| ⇔x3 + x2z - x2z - xz2 | = y2z | ||

| ⇔x3 - xz2 | = y2z | ||

And that last equation is simply h = 0, which we know is true. Since each of

these lines are connected by iffs, we can follow the proof backwards and get that

both formulas are equivalent (when y,x + z≠0). Which means that we can

simply define the inverse of ϕ as

| (x,y,z) |

|

Almost forgot to check: Is that exhaustive? y≠0 and x + z≠0 doesn't look

exhaustive. But if you think about it, if you had y = 0 and x + z = 0 at the

same time, these just determine the point (1, 0,-1), which we know is not in

the domain (man, this is like the third time the exclusion of that point has come

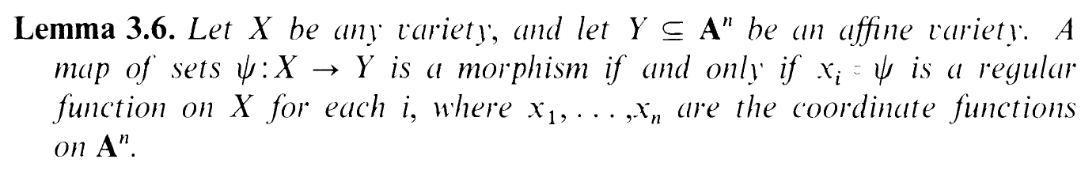

in handy, lol). So the map is defined, and we know it's a morphism thanks to

lemma 3.6:

(and the definition of a rational function).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Okay, that was kind of handwavy. First of all, half my argument doesn't work

because Y is not known yet to be a variety (irreducible), only an algebraic set. So

half the theorems we have about "morphisms" fall short. I need to show that

Y is irreducible before I can do much. Wellllll, we can still use Lemma

3.6. If I denote the inverse as δ and write the map as δ : X → P3,

then.... Oh.... that's P3, not A4... Lemma 3.6 wants it to be A4...............

Wait, uhhhhh, how the fuck do you do this exercise? LOL. Welllllll, I think

it's fairly believable that both δ and ϕ are closed maps, so they make a

homeomorphism of X ≃ Y . Now, unlike Y , X is clearly irreducible (open set in

a variety), hence the homeomorphism says that Y is irreducible. OKAY. COOL.

Y is a variety! Yaaaaay. Which means that I can safely call ϕ a morphism.... But

I still don't know what enables me to call δ a morphism? Can't I actually just

appeal to the definition of morphism? Now that I think about it... what's even so

special about Lemma 3.6? Whatever, fuck this. Yeah, FUCK THIS. I'm just

being overtechnical. If δ isn't a morphism, then I'LL EAT MY RIBBON.