I.3.13

5/7/2021

Attention Required! — Cloudflare One more step Please complete the security check to access–

*Loads barrel*

*Cocks gun*

*Aims*

BANG BANG BANG BANG BANG BANG

BANG BANG BANG BANG BANG BANG

BANG BANG BANG BANG BANG BANG

BANG BANG BANG BANG BANG BANG

BANG BANG BANG BANG BANG BANG

BANG BANG BANG BANG BANG BANG

BANG BANG BANG BANG BANG BANG

BANG BANG BANG

Whew. Sorry, was just letting off some steam. Anyway, today's exercise asks us to

prove 3 separate things. Let's start with the first:

PART 1:

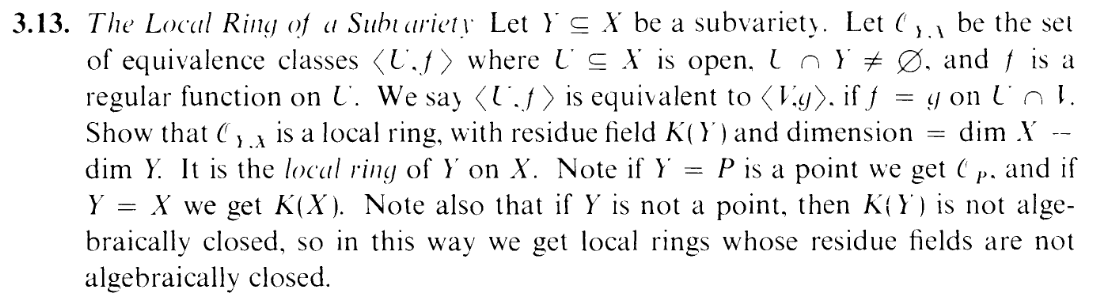

Y,X is a local ring

Y,X is a local ring

I.e. we need to show that it has a unique maximal ideal. Now, if P ∈ X were a

point, then the maximal ideal of

P,X are all the elements that vanish at P.

Hence, let's guess that the maximal ideal of

P,X are all the elements that vanish at P.

Hence, let's guess that the maximal ideal of

Y,X are all the elements that

vanish on Y . Define:

Y,X are all the elements that

vanish on Y . Define:

| M | = {< U,f >∈

Y,X|f vanishes on Y } Y,X|f vanishes on Y } |

One thing I have to check is that this set is well defined. I.e., if < U,f >=< V,g >, then if f vanishes on Y , does g also vanish on Y ? The answer is yes, thanks to remark 3.1.1 (f = g = 0 on U ∩V ∩Y which is an open set of Y ). Also, M is clearly an ideal.

So is it maximal? If J ⊋ M, is an ideal, then it would have to contain some < U,f > where f does not vanish on Y . So f(Q)≠0 for some Q ∈ Y . Our goal is to invert f, so we can produce 1. Let V be an open set of X containing Q such that f = g∕h for polynomials g,h. Then Z(g) ∩ X is closed in X, so W = X - (Z(g) ∩ X) is a nonempty open set in X (it's nonempty because Q ∈ W!). V ∩ W is a nonempty open set that intersects Y (since it contains Q), and note that f = g∕h on that set, with g never vanishing on it. Hence we can define < V ∩ W,h∕g > as en element of

Y,X. Multiplying this by < U,f > produces a 1 in the ideal so

J = (1). Hence, every ideal is contained in M (unless its (1)). DONE.

Y,X. Multiplying this by < U,f > produces a 1 in the ideal so

J = (1). Hence, every ideal is contained in M (unless its (1)). DONE.

PART 2: The residue field of

Y,X is K(Y ).

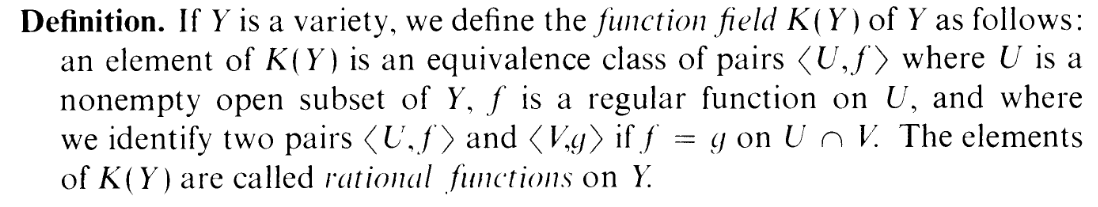

Y,X is K(Y ). Oh, btw, here's the definition of a function field:

(dw: this is, effectively, the first time I've seen it too)

So we want to show

Y,X∕M ≃ K(Y ), so the typical way of doing this on this

blog is to make a morphism

Y,X∕M ≃ K(Y ), so the typical way of doing this on this

blog is to make a morphism ϕ :

Y,X Y,X | → K(Y ) |

whose kernel is M. And the "natural" choice of a map would be

| < U,f > |

< U ∩ Y,f > < U ∩ Y,f > |

So suppose < U,f >∈ M. Then f vanishes on Y , so

| < U,f > |

< U ∩ Y,f > < U ∩ Y,f > | ||

| =< U ∩ Y, 0 > |

hence M ⊂ ker ϕ

For the reverse inclusion,

| < U,f > | ∈ ker ϕ | |||||

ϕ(< U,f >) ϕ(< U,f >) | =< W, 0 > | |||||

< U ∩ Y,f > < U ∩ Y,f > | =< W, 0 > | |||||

f f | = 0 on U ∩ W ∩ Y | |||||

f f | = 0 on Y |

PART 3: dim

Y,X = dim X - dim Y

Y,X = dim X - dim Y I have no idea how to do this lol. I am looking up a solution, brb.

Okay, I got it (...still took me a while since the solution skipped most of the details). You have to do the "reduce to affine" thing we did last time, plus theorem 1.8A.

Let's start by showing that reducing everything to affines works. I.e. assume that

LEMMA 1: If X is an affine variety and Y is a subvariety, then dim

Y,X = dim X - dim Y

Y,X = dim X - dim Y I'll prove this at the end, but let's assume we have it for now. Like last time, we need to show that everything works for quasi-affines, projective varieties, quasi-projectives, etc. First, this lemma will help us:

LEMMA 2: If X is any variety and Y is a subvariety and U is an open subset of X, then dim

Y ∩U,X∩U = dim

Y ∩U,X∩U = dim

Y,X

Y,X The proof is obvious.

Now, let's go through them:

LEMMA 3: If X is a quasi-affine variety and Y is a subvariety, then dim

Y,X = dim X - dim Y

Y,X = dim X - dim Y PROOF:

X is an open subset of some affine variety Z (so X = Z), so

dim

Y,X Y,X | = dim

Y ∩X,Z∩X Y ∩X,Z∩X | |||||

= dim

Y,Z Y,Z | (LEMMA 2) | |||||

| = dim Z - dim Y | (LEMMA 1) | |||||

| = dim X - dim Y | ||||||

| = dim X - dim Y |

Done with LEMMA 3. Now,

LEMMA 4: If X is an projective variety and Y is a subvariety, then dim

Y,X = dim X - dim Y

Y,X = dim X - dim Y PROOF:

Using the usual isomorphism, we have an open set U such that U ∩ X is an affine variety. Hence

dim

Y,X Y,X | = dim

Y ∩U,X∩U Y ∩U,X∩U | |||||

| = dim Y ∩ U - dim X ∩ U | (LEMMA 1) | |||||

| = dim Y - dim X | (2.7b) |

LEMMA 5: If X is an quasi-projective variety and Y is a subvariety, then dim

Y,X = dim X - dim Y

Y,X = dim X - dim Y PROOF: Same idea as LEMMA 3.

Okay, so basically if we show LEMMA 1, we're done (moral of the story: reducing to affine helps a lot, especially for dimension arguments)

They define α = {f ∈

(X)|f vanishes on Y }, and (since this is apparently

prime), they apply 1.8A:

(X)|f vanishes on Y }, and (since this is apparently

prime), they apply 1.8A: htα + dim

(X)∕α (X)∕α | = dim

(X) (X) | (1) |

htα htα | = dim

(X) - dim (X) - dim

(X)∕α (X)∕α | (2) |

Now, since we're working with affines, we know that

dim

(X) (X) | = dim A(X) | |||||

| = dim X |

So we can rewrite (2) as

| htα | = dim X - dim

(X)∕α (X)∕α | (3) |

And here's something else: dim

(X)∕α ≃ dim Y .... Errrrm... EXERCISE

LEFT TO READER (hint, if you think about it, the left hand side is just the

coordinate ring of Y .... I think).

(X)∕α ≃ dim Y .... Errrrm... EXERCISE

LEFT TO READER (hint, if you think about it, the left hand side is just the

coordinate ring of Y .... I think). So now, we can rewrite (3) as

| htα | = dim X - dim Y | (4) |

Yeah, you can guess where this is going. Since

Y,X is a local ring,

dim

Y,X is a local ring,

dim

Y,X = htM. So if we show that htM = htα, we're done.

Y,X = htM. So if we show that htM = htα, we're done. In fact, it is very easy to produce a bijection

|

and that finishes off LEMMA 1, and thus this exercise.

I'M BAD @ MATH.