I.1.8

12/17/2020

Well, it has been 2 weeks since my last post on this blog. 2 weeks. 2 weeks is the timeframe I gave

myself to finish an entire section, yet 2 weeks have been spent procrastinating on a single exercise. 2

weeks of mental deterioration, recession into inactivity, aimlessness. You'll note that I've skipped 1.7. That is because 1.7 is a 4-part exercise about Noetherian rings. Yes, I will get around to it,

but I'm not going to use that as my welcome back party. Instead, let's get intimate with this cozy

1-parter.

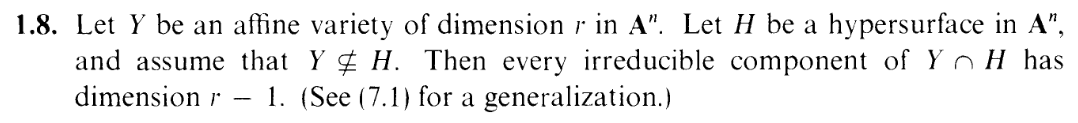

Welcome to 1.8! Give the idea some thought, reader. Does it not check out intuitively? Set n=2, consider the

1-dimensional unit circle, intersect it with a line, and you get two points: two irreducible subsets each with a

dimension of 0, as you'd expect. Set n=3, consider the 2-dimensional unit sphere, intesect it with a plane, and you

get an circle: a 1 dimensional curve, just as you'd expect. Dimension in algebraic geometry works the way you

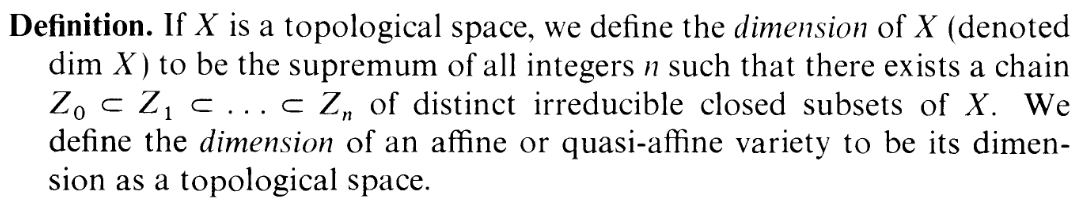

expect. Now let's have a look at the explicit definition!

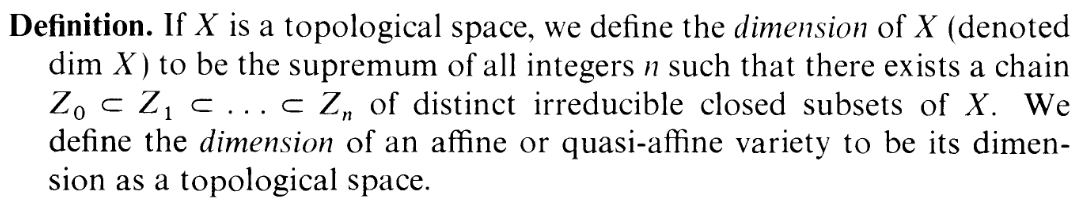

Uh, well... That's not as intuitive looking as I expected. How does something this technical give us all the nice

results from above? How does something this abstract connect to spheres and circles? Doesn't matter, cause I'm

going to go through this proof by forcing my way through notation instead of seeing the big picture.

HAH. By the end of this post, we'll have learned nothing. There is a right way and wrong way to do

math. The right way is to collaborate, have an open mind, and think about the "why" behind what

you're doing. But you came here to see the wrong way, right? Yes: We came here to lose. Let's do

it.

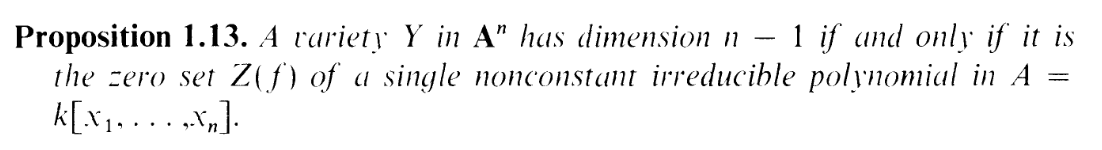

Well, we already have the Y = An case already sorted out for us:

(substituting "H" for Y in the proposition, lol) We're already partway there, ain't we?

Well, okay, let's try it out. I'll denote A = k[x1,...,xn] for this exercise.

We know that Y = Z(P) for a prime P (since Y is an affine variety), with dimY = r. We know that H = Z(f) for

an irreducible poly f. And from the proposition above, dimH = n - 1.

So we can write

| Y ∩ H | = Z(P) ∩ Z(f) | |||||

| = Z(P + (f)) | EZ to prove, I swear | |||||

| I(Y ∩ H) | = I(Z(P + (f))) | ||

=  | |||

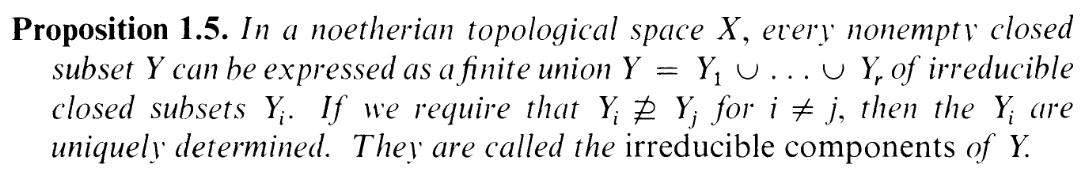

Oopsy doopsy, we've got a radical that we can't quite get rid of, cause the sum of prime ideals is not necessarily prime, nor radical. What do, bros? well, the exercise tells us we need to derive the dimension not of Y ∩ H but of each irreducible component of Y ∩H (if P + (f) were prime, then Y ∩H would itself always be irreducible, so the phrasing of the exercise wouldn't make sense... although this took me like 30 minutes to realize) so let's split it up according to:

(the prop works here cause any subspace of a Noetherian space is Noetherian, check it), i.e. we have

Y ∩ H = S1 ∪

∪ Sl

∪ Slwhere each Si is an irreducible component. We need to show that each of these have a dimension of r - 1, so we can assume without loss of generality that i = 1.

So, letting d = dimS1, I have to show that d = r - 1. Now, I got stuck here for... a while. And my lightbulb moment was to split this into the cases d < r - 1 and d > r - 1 and obtain a contradiction in each.

First, a lemma that I'd end up needing later: I'll show that we can just consider the case S1 ⊊ Y (Note the slash on the line, proper inclusion. Sorry, it's hard to see). Why? Because *AHEM* otherwise we'd have S1 = Y

Y ∩H = Y

Y ∩H = Y  H ⊂ Y but since the exercise says Y ⊈ H

H ⊂ Y but since the exercise says Y ⊈ H Y ≠H, this

means that the inclusion has to be strict, i.e. H ⊊ Y

Y ≠H, this

means that the inclusion has to be strict, i.e. H ⊊ Y  I(H) ⊋ I(Y )

I(H) ⊋ I(Y ) (F) ⊋ P

(F) ⊋ P P = (0)

P = (0) Y = An and this

case was already covered by Prop 1.13 as discussed earlier. *Wipes fucking forehead* You've heard of run-on

sentences, but you ever seen a run-on proof?

Y = An and this

case was already covered by Prop 1.13 as discussed earlier. *Wipes fucking forehead* You've heard of run-on

sentences, but you ever seen a run-on proof? Okay. Now with that settled, time to handle

CASE 1: d > r - 1

Then there exists a chain

S1 = Zd ⊋

⊋ Z0

⊋ Z0of irreducible closed subsets of S1.

But if they're irreducible closed subsets of S1, then they're irreducible closed subsets of Y (since S1 itself is closed).

Note, from the lemma we had Y ⊋ S1 = Zd, and Y is an irreducible closed subset (a variety), so we can make the chain

Y = Zd+1 ⊋ Zd ⊋

⊋ Z0 of irreducible closed subsets of Y , making

⊋ Z0 of irreducible closed subsets of Y , making | dimY | ≥ d + 1 | |||||

| > (r - 1) + 1 | from the assumption of this case | |||||

| = r | ||||||

i.e. dimY > r, contradicting dimY = r.

So case 1 is done, now we can handle

CASE 2: d < r - 1

Okay, for this case, you have to give the fuck up because you're not going to get anywhere with it lolololololololololololololol. Look: We have an upper bound on the dimension. I.e. we know that the chain of irreducible closed subse–fuck this is a pain to type (and it was more annoying to write in a notebook)–anyway, we know that the chain of "irreducible closed subsets" of S1 is at most r - 2. But don't you see how unhelpful this is? Because the maximum chain may have a length of r - 2, but it could also have a length of 0 Unlike case 1, I can't say "there IS a at least a chain of length x" and do something with that chain. At most I can say "there IS at least a chain of length 0" but this is unhelpful because there's ALWAYS at least a chain of length 0. The trivial chain is always a chain.

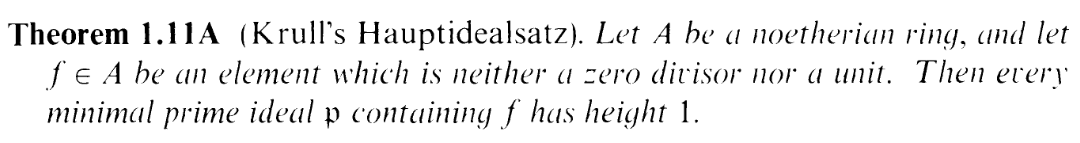

Well, basically, I floundered around in this "CASE 2" for an hour or so before giving up and procrastinating on the exercise for 3 more days. Now, in order to prevent this floundering from extending into another 2 weeks of idle self-discovery (2 weeks to figure out, "Oh, right I'm a loser"), I decided to look up the solution. It hurts to say that I had to do it, but I did. However, the only hint I used from the solution was the term "minimal prime ideal" and something about it having a "height of 1". Seriously: As soon as I saw "minimal prime ideal", I realized, "Fuck. That's what I missed". I did not need to look at the rest of the solution.

Soooo my "lightbulb moment" was actually a darkbulb moment. A pinkbulb moment, a holeinmyheart moment. But I nevertheless pulled the pull chain switch for this post: you, reader, are privy to my failures. I could cry in the site diary about my incompetence, or I can show you my incompetence. Light it up, baby. Welcome to Hartshorned. And let's make you privy to a pinch of my emotion: I'm angry that I did not realize this "minimal prime ideal" thing. You see, S1 is not just an irreducible closed subset of Y ∩ H, it's a MAXIMAL irreducible closed subset (i.e. an irreducible component) of Y ∩ H. So its corresponding ideal, J = I(S1) is a MINIMAL prime ideal containing I(Y ∩ H). Duh, right? I did not take maximality of S1 into account, and if I did I could have maybe done the whole thing without a hint. I'm angry that I didn't realize that. Now, there's still quite a bit of confusing notation to dick through here, but it's dickable.

Now, you know how the radical in I(Y ∩H) =

is annoying? Well, we can get rid of it, sort of. Because J

is not only the smallest prime ideal containing

is annoying? Well, we can get rid of it, sort of. Because J

is not only the smallest prime ideal containing  , it's the smallest prime ideal containing P + (f). Why?

Because

, it's the smallest prime ideal containing P + (f). Why?

Because  is the intersection of all the prime ideals containing P + (f). If we had a prime ideal Q such that

J ⊃ Q ⊃ P + (f), then since Q ⊃ P + (f), Q ⊃⋂

primeS⊃P+(f)S =

is the intersection of all the prime ideals containing P + (f). If we had a prime ideal Q such that

J ⊃ Q ⊃ P + (f), then since Q ⊃ P + (f), Q ⊃⋂

primeS⊃P+(f)S =  . but J is the smallest prime

containing

. but J is the smallest prime

containing  , so Q = J.

, so Q = J.Hence, J is the smallest prime ideal containing P + (f), i.e. it is the smallest prime ideal containing both P and (f) (since P + (f) is itself the smallest ideal (note: I keep saying "smallest" when minimal is a more appropriate word. Sorry) containing P and (f)).

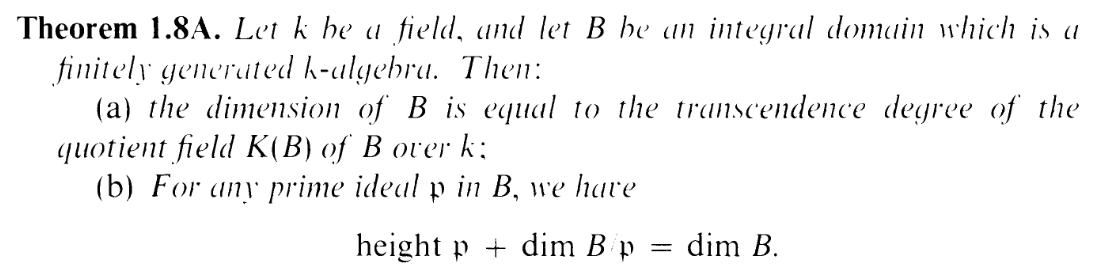

Why does this matter? Theorem 1.8A(b) has been used numerous times in dimension arguments,

so with all the different moving parts in this problem, we'll want to try using it here. Now, the naive approach would be to set B = A and 𝔭 = J, giving us

| htJ + dimA∕J | = dimA | ||

htJ + d htJ + d | = n | ||

But this isn't very helpful because it's difficult to nail down htJ. I'm aware that it's a minimal prime containing P + (f), but how does that help me nail down the height?

So I got stuck, and scrolled through the book for a while for a mention of "minimal prime ideal" and found this:

Oh. OHHHHHHHH. Remember the "height of 1" from the hint? Now, the situation in this proposition isn't exactly the situation we have. We have J is a minimal prime containing P + (f), not (f). But is there any way we can get rid of the P? We can, by quotienting it out. Heck, I already know that dimA∕P = dimY = r, so let's give this a shot.

Now we use the fact that ideals I in A that contain P correspond naturally to ideals in A∕P via the quotient map I

π(I) = I∕P. Hence, since J is the smallest prime ideal in A containing P, π(J) is the smallest prime ideal

that contains π(P + (f)) in A∕P. Fuck, fuck, fuck, this algebra is fucking my ass. ARRRRGH. We're almost

done. Almost fucking done for fucks sake. It's easy to check that π(P + (f)) = (π(f)) = ([f]), so the

theorem tells us that π(J) has a height of 1 as long as π(f) = ([f]) is a nonunit nonzerodivisor. For

now, let's just assume that it is. Then, plugging in B = A∕P and 𝔭 = π(J) into Theorem 1.A(b), we

get

π(I) = I∕P. Hence, since J is the smallest prime ideal in A containing P, π(J) is the smallest prime ideal

that contains π(P + (f)) in A∕P. Fuck, fuck, fuck, this algebra is fucking my ass. ARRRRGH. We're almost

done. Almost fucking done for fucks sake. It's easy to check that π(P + (f)) = (π(f)) = ([f]), so the

theorem tells us that π(J) has a height of 1 as long as π(f) = ([f]) is a nonunit nonzerodivisor. For

now, let's just assume that it is. Then, plugging in B = A∕P and 𝔭 = π(J) into Theorem 1.A(b), we

get| dimA∕P | = htJ∕P + dim(A∕P)∕(J∕P) | ||

| = htJ∕P + dimA∕J | |||

| = htJ∕P + dimS1 | |||

| = htJ∕P + d | |||

r r | = htJ∕P + d | ||

d d | = r - htJ∕P | ||

So if we ust show that π(f) is a nonunit nonzerodivisor, then we get that π(J) = J∕P has a height of 1, making d = r - 1.

ALMOST

FUCKING

DONE.

So, let's finish it off.

LEMMA: π(f) is a nonzerodivisor:

Well, since P is prime, A∕P is an integral domain, so it has no nonzero zerodivisors. So if π(f) is nonzero, it's not a zerodivisor. And [f] = [0]

f ∈ P

f ∈ P (f) ⊂ P

(f) ⊂ P Z(f) ⊃ Z(P)

Z(f) ⊃ Z(P) H ⊃ Y contradicting the Y ⊈ H assumption

from the exercise. So we're done.

H ⊃ Y contradicting the Y ⊈ H assumption

from the exercise. So we're done.LEMMA: π(f) is a nonunit:

[f][g] = [1]

[fg - 1] = [0]

[fg - 1] = [0] fg - 1 ∈ P

fg - 1 ∈ PNow, err, I got worried here for a while. How does this give you a contradiction? Well, 1 is a special term in a ring, so let's isolate it:

fg - 1 ∈ P

fg - 1 = p (where p ∈ P), so fg -p = 1 But this means that (f) + P = (1)

fg - 1 = p (where p ∈ P), so fg -p = 1 But this means that (f) + P = (1) Y ∩H = An

Y ∩H = An H = An

a contradiction since H is a hypersurface. DUN.

H = An

a contradiction since H is a hypersurface. DUN.And there you go. I don't know if I did this in the most optimal way, but it's done.

Now that we're done with the exercise, it's time for some introspection. I spent 3 days on this exercise. No, I spent 3 hours working on it and 3 days procrastinating on it. But that is 3 days spent working on it. Procrastination is work. And this exercise should not have taken that much work. Now, you remember me dismissing any intuitive interpretation on "dimension" at the beginning of this post? "Let's just BS through the notation", I proclaimed. Well, it's that mindset that fucked me.

I was angry that I missed using the maximality of S1. I was angry that I needed to look up that hint. But, you see, if I put an intuitive lens on what I was doing, I may have been able to realize it on my own. Let's look at the definition of dimension again:

"What does this have to do with spheres and circles?" I asked. Okay, let's find out. Take X to be a sphere in An. The dimension of X should be 2, intuitively. Does it check out? Well, I need a chain of irreducible closed proper subsets of it. What closed surfaces exist in the sphere? In particular what are the "biggest" ones, since we want the chain to be as long as possible? Well, X itself THE biggest, but that's not a proper subset, so it doesn't count. What else is there? Well, the "biggest" ones I can think of are circles in the sphere. Ah. The biggest surfaces are all 1-dimensional: The set below X itself in the chain has to be a circle in the sphere. And what are the "biggest" surfaces below the circle in the chain? Other than the circle itself, the best you can do would be points in the circle: 0-dimensional surfaces. So the maximum chain you can make is:

X = Z2 (the sphere) ⊋ Z1 (a circle in the sphere) ⊋ Z0 (a point in the circle)

So the definition is actually fairly intuitive. Each proper inclusion represents the ability to fit a lower dimensional surface into your surface. The number of dimensions you can go down is the dimension of the surface itself. If this picture guided me, I might have realized that r - 1 means we're going down 1 from r = dimY , so the maximality of S1 in Y would be important. If I didn't ignore the intuition, I might have been able to do it without a hint.

Well, the algebra that ensues after that is a mess, but who knows, maybe that also becomes more clear if I think about it. For example: Since S1 is 1 down from Y , it's actually a hypersurface in Y : its ideal J∕P in A(Y ) = A∕P would probably have to be principal prime ideal, J∕P = ([g]) for an irreducible [g] ∈ A∕P. In fact, I believe this [g] would be a factor of [f] itself (very much confirming the "smallest prime containing ([f])" statement). If I thought about things pictorially instead of stubbornly, aimlessly manipulating algebra equations, the exercise basically solves itself. The thing that was getting in the way was me.